(I've included links back to the original 2008 articles - feel free to browse back and read them but do bear in mind that some information in them may now be slightly out of date, especially where specific models and future speculation is involved!)

Exposed camera glass

The investigation which sparked off the whole article series, fired by my experiences on the Nokia N95 8GB, that, for average camera phone use, even quite bad scratches on the outside camera glass make negligible difference to the quality of the finished photos - the reduction in light levels just isn't significant and the focussing point is far, far beyond the scratches themselves. The only caveat to this is when shooting into the sun or using flash, when the scratches cause lens flare and possibly unwanted lighting effects.

With almost all of today's camera-toting smartphones having unprotected camera glass, much the same results apply, although the materials used in Nokia's cameras may have improved to the point where scratches are less likely. In the N95 8GB's case, the scratches were mainly in the anti-reflective coating - which I had to remove in the end. These coatings have got better over the years and better 'baked' in. And, in the case of the new camera flagship, the N8, the camera 'glass' is not only real glass but toughened.

Mind you, you're still advised to wipe the camera glass with a tissue before taking photos or video, since fingerprints can make far more of a mess of your focussing and clarity than scratches ever could.

I don't see the situation changing either. Although I still favour proper camera glass protection, the extra few millimetres needed for the mechanism works against slimming down the phone's overall form factor - and Nokia have stated that they prefer to keep the camera always 'open' for use in augmented reality and other camera-related applications. Take this excuse with a pinch of salt! 8-)

(further reading - original Part 1)

LED or Xenon flash?

In the original series of test shots, I demonstrated quite conclusively the power of Xenon. Yes, dual LED flashes were naturally brighter than single LED, but even so they're many times weaker than Xenon. Secondly, the long shutter time needed for working with LED flash means that subjects in motion end up badly blurred - anyone taking a LED flash photo at a party or disco will know bad this blurring can get. In contrast, Xenon flash 'freezes the instant' superbly.

When the original piece was written, only the Nokia N82 and Samsung G810 had Xenon flash - we've seen a slight resurgence in Xenon, but only marginally so. The N8 flagship has Xenon flash, which we saw in the N8 review part. The now discontinued Sony Ericsson Satio also had Xenon but didn't make best use of it. Away from Symbian, the Android-powered Motorola Xt720 (also effectively discontinued, sadly, in that it's not going to be updated any more) and the new Windows Phone 7-powered HTC Mozart 7 both have Xenon flashes, but in each case you get the impression that they're models put out to 'test' the market and not part of some strategic push to improve the lot of camera phone photographers across the world.

Partly this is down to cost and size - the Xenon bulbs and bulky capacitors do have an impact on form factor and build cost - and partly this is down to some inherent advantages of LED flash. Specifically that they can be run continuously, giving a convenient 'torch' mode or even a video light for night time videos. The results are rarely ideal, but are better than nothing, since Xenon 'flashes' are strictly that, i.e. they flash and then it's a two second recharge for the next one.

Horses for courses, I guess. Again, I don't see the situation changing much - the ratio of LED to Xenon at around 10 to 1 will be maintained, though it's puzzling to me why we haven't seen at least one high end model with Xenon flash for stills and a LED flash for torch and video light.

(Further reading - the original Part 2)

The Megapixel Myth?

I stand by this one, with a caveat. All other factors (light, etc) being identical, for most people's purposes, there's seemingly little point in chasing after higher megapixel numbers - at typical display or print dimensions, you simply won't be able to tell the difference. 3 or 5 megapixels seems to be a sweet spot here - 8 megapixels and above simply aren't needed for average users.

Which is a little disingenuous, since all other factors are unlikely to be identical. Even low end camera phones now have 3 megapixel sensors, but that doesn't mean that they have decent optics or a large sensor. It seems that you have to go to at least 5 megapixels and often 8 before you find a device with a decent camera in it in 2010. So, where we had the 3mp Nokia N93 in 2006, with top end everything, the equivalent model in 2010 is the N8 with a massive 12 megapixel resolution.

Partly this is because there has been a constant (and slightly unnecessary) bullet-point battle between manufacturers to try and out-spec the competition. And, I'll admit, partly because there are some slight advantages to going to higher and higher resolutions. Firstly, display resolutions on both monitors and TVs has increase a lot in the last four years and having super large resolution snaps means that you can put on decent slide shows without ugly artefacts. And secondly, the flexibility to crop out a 5 megapixel section from a 12 megapixel full image is hugely satisfying. It means you can photograph things under less than ideal circumstances (e.g. not being able to get close enough) and then fix things later at the editing stage and still end up with a decently sized image.

A typical 12 megapixel to 5 megapixel crop - you get the idea. And final resolution is still good enough for a 6" by 4" print etc.

(Further reading - the original Part 3)

Quality of optics

In my original tests, I found only a negligible difference in the quality, with the sensor fitted and the software algorithms used playing an equally important part. I concluded that branded optics might be a clincher when agonising over two phones of similar camera spec, but not to use this as the be all and end all of choosing a camera-toting phone in the first place.

However, I should add a big rider to all this - I was talking about Nokia-branded devices, all of which have cameras of a certain minimum quality. Since then I've seen many 3 and 5 megapixel camera-toting smartphones from manufacturers from the Far East which have had quite appalling optics and sensors, such that my old 1.3 megapixel Nokia 6630 would best them in a head to head comparison. HTC, ZTE and LG are some of the worst offenders.

A far better photo than would be possible on many 2010 smartphones from Eastern manufacturers. This photo was shot on... the 2004 Nokia 6630!

A far better photo than would be possible on many 2010 smartphones from Eastern manufacturers. This photo was shot on... the 2004 Nokia 6630!

For quality then, there's no substitute for reading reviews and looking at photo samples - you certainly can't go by resolution!

(Further reading - original Part 4)

Optical zoom

In the original article, I looked at the difference optical zoom makes and asked the question "Is it better to have optical zoom or just much higher resolution?" The answer, I concluded, is that neither is 'better'. Zooming in by 3 times with a 3mp camera (e.g. on the old Nokia N93) produces detail roughly equivalent to that from a 8mp camera unit. However, the use of optical zoom means lower light levels (one extra piece of glass in the way of the photons), greater expense in terms of hardware build costs, greater bulk in the camera itself and a much greater susceptibility to 'camera shake' (shown below). I concluded that these were all reasons why, despite the apparent desirability, we probably wouldn't see many camera phones with optical zoom in the future.

It seems that I was right - after the almost unheard of (and manufacturer-abandoned) Samsung G810, there haven't been any smartphones with optical zoom. Whereas higher and higher intrinsic resolutions seem to be more easily attainable and give more flexibility in real life products.

Plus it should be noted that optical zoom's other main selling point, the use of zooming in video mode, has now been effectively equalled in software by Nokia in their groundbreaking N86 and N8, both of which use real time interpolation of information from the whole of their large sensors in video mode to produce up to 3x zoom without any loss of quality.

(Further reading - the original Part 7)

Video focus differences

In this part, I was particularly interested in the way Nokia preset the focus in video mode differently for different devices. The N95 and N82 set their focus at a couple of metres and as a result had a depth of field from a metre to infinity, whereas many of Nokia's less-camera-centric phones had less effort put in on this front and as a result had the lens focussed on infinity in video mode, meaning that anything closer than about 20 metres was blurred to some degree. So that's videos of people and pets out then. This continued right up through the disappointing N97 and N97 mini, sadly. The N86, designed by the same guy as the N82, put things right again with a preset focus, as did the recent N8, again with Damian D at the helm, both able to shoot anything from about a metre to the horizon with perfect clarity.

Away from Nokia, manufacturers have been experimenting with different focussing systems in video mode. In the last year or so we've seen the iPhone 4 with tap-to-focus - all very well but does require quite a bit of manual intervention to keep your subject clear for anything other than a static shot; the Symbian-powered Sony Ericsson Vivaz with continuous auto-focus - again all very well, but the constant 'hunting' for focus whenever you change subject can be (visually) very distracting; and a host of devices with initial pre-focus - again only any good for static shots, since as soon as you pan away to a different subject your focus is lost.

I've tried all the above systems and would still plump for the N95/N82/N86/N8 system of a static (or, in the N8's case, hyperfocal) focus point and a decent depth of field - there's nothing needed from the user after pressing the shutter button to start shooting and there are no visual artefacts to get in the way.

A recent addition to this subject has been the new EDoF cameras from Nokia, in the likes of the E5, C6-01, C7 and E7, with the EDoF electronics working just as well in video mode as in photo mode. Effectively, this carries on the philosophy above, but gives an even greater depth of field, so everything from about 50cm to infinity is in focus all the time while shooting.

(Further reading - the original Part 9)

Lens and sensor size

In the original article, comparing the Nokia 5800 with an N95 'classic', I showed how a smaller aperture and correspondingly smaller sensor led to dramatically different levels of digital 'noise' in low light conditions. Quantum physics even got a mention! These effects are even more dramatic for video capture, where getting as many photons of light to register per 1/30s frame is vitally important.

Nothing's really changed since, though we have now seen the N86 and N8 with bigger and bigger lenses and sensors, both capable of usable evening video capture, even if purists will still find fault with low light stills. And technological advances in sensor manufacture have led to some phones with lower digital noise, notably the 'backside illuminated sensor' of the iPhone 4, among others.

But for evening video (parties, pub, events), the rule of thumb still holds - the smaller the camera lens (it's easy to see this from the outside), the smaller the sensor is likely to be and the (dramatically) worse its low light stills and video capture will be.

(Further reading - original Part 10)

Scene modes and Settings

In the original piece, I looked at the various Scene modes and additional settings in Nokia's Camera applications - are any of them needed? It turned out that almost none of them are needed. I demonstrated benefit from using 'Sports' mode and from tinkering with 'White balance', but for most practical purposes you need never feel guilty about simply leaving everything on 'Automatic' all the time. Phew!

(Further reading - original Part 12)

The soundtrack matters

A vital part of video capture on phones is the audio soundtrack (I often state that audio quality is more important than picture quality, since bad audio makes a piece unwatchable) and this is an area where Nokia, in particular, have always been very strong, using higher quality microphones than many other manufacturers, even today in 2010.

The latest tech trend from Nokia's R&D labs is the use of MEMS 'digital' microphones. Rather than have a traditional analogue microphone connected to an A to D converter, a MEMS microphone is a chip in its own right, mounted on the phone's motherboard. The result is dramatically crisper audio capture, provided care is taken in terms of handling and encoding the digital audio stream. Nokia got it right with the N8, but the C7's audio is currently sub-par and I'm guessing firmware tweaks are needed to tune the encoding software properly.

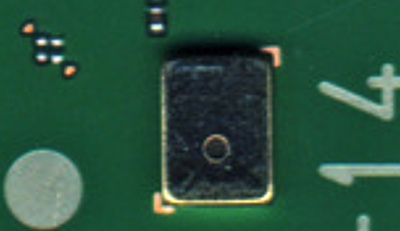

The MEMS microphone (digital microphone on-a-chip) on the Nokia N8 motherboard

I tested the HTC Desire HD the other day, a top of the range Android flagship - with 8kHz mono audio capture using an analogue microphone. The result was pretty awful in terms of audio soundtrack to captured videos. The bare minimum for 2011 should be 44 or 48kHz sampled digital audio capture using MEMS chips - and preferably in stereo. It's really not that hard to do or expensive to implement.

Can EDoF rise to the challenge?

One of the biggest controversies around these parts has, of course, been Nokia's decision to use EDoF cameras in all but its camera flagship models. There's no doubt that EDoF is better than dumb 'fixed focus' camera units, but we've all got very used to Nokia's rather good auto-focus cameras over the last four years, with macro possibilities (including business card scanning) and plenty of scope for arty photographs with specific depth of field. Which means the acid question is "Is EDoF good enough?".

You're asking the wrong person, I'm afraid. Impressed though I've been by EDoF samples in the past, Almost everything I do in terms of photography with my phone involves some degree of specific focussing. Even if it's just snapping my daughter's latest culinary creation or our Christmas tree. And the very fact that you too are asking this question means that you're possibly the wrong person too. We need to get feedback from 'normobs', buyers of the likes of the C6-01 and C7 who don't have any specific photographic pretensions.

EDoF sample taken on the 3 megapixel E55 - amazing really. Will EDoF satisfy the masses? There's a good chance, you know...

EDoF sample taken on the 3 megapixel E55 - amazing really. Will EDoF satisfy the masses? There's a good chance, you know...

I've been a little shocked by just how whole-heartedly Nokia has thrown itself into EDoF across its range of smartphones this year. Time will tell whether Nokia should have held back and used an auto-focus/EDoF mix or not. Watch this space!

Steve Litchfield, All About Symbian, 1 Dec 2010

PS. For examples of photos and videos taken on the Nokia N86 and N8, see also The Phones Show.