The party trick though. Playing on most people's preconceptions that touchscreens are fragile affairs, when talking about my phone (hey, people do keep asking me what I'm using, etc.) I like to ask to borrow a kitchen knife. With mouths agape, they watch as I then casually mention that my N8 has Gorilla glass and I slash away at the display. "It's very tough", I say, as I literally stab at the screen with the point of the knife. For good measure, I then rap the phone screen sharply against the nearest hard furniture corner.

As a party trick, it impresses. But such a cavalier attitude to touchscreens wasn't always possible.

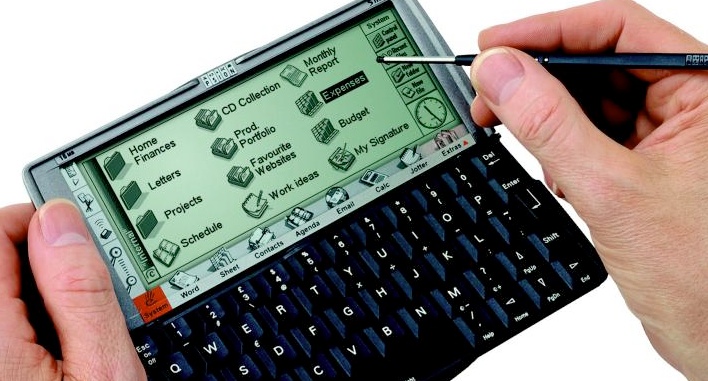

My first encounter with touchscreens was on the Psion Series 5, running EPOC, the oldest living direct ancestor of today's Symbian smartphones. Each Psion came supplied with a plastic stylus (though various aftermarket alternatives were also available, including some made from aluminium) and the idea was to use it to tap the on-screen command buttons and menus, swipe across text to highlight it and (occasionally) sketch out a diagram using the rudimentary drawing application.

It's worth noting that most users, including myself, quickly got into a very bad habit (albeit a forward-looking one, as we shall see). Because the keyboard was always open, we'd treat the Series 5 as a mini-laptop and have both hands actively employed. The stylus was rarely to hand when needed (unlike in the press shot below!), so I used to do most of the touchscreen tapping using the tip of my finger or, more usually, the back of a fingernail (to try and minimise the amount of finger grease that got transferred). Using one's finger was frowned upon, officially, but many people did it anyway.

A year or so later, I also got my first Palm, also with a touchscreen. As with the Psion, the display was monochrome and the touch layer resistive, of course, meaning that it was soft and fragile. Get a speck of dirt on the end of your stylus, swipe it across the screen and the display was marked for the lifetime of the device. Unsurprisingly, there was a thriving market in screen protectors (though cut-to-size OHP transparencies did the job pretty well) and in silicone-based screen polishes. I still have a bottle or two of the latter around the office....

Time moved on and Psion gave up on the PDA market - sadly. Microsoft got in on the action with their Pocket PC-based PDAs, also with resistive touchscreens, getting ever larger, up to 4" in some cases, matching today's large screened smartphones. Palm went through their own purple patch with the V and Tungsten ranges, with screens again getting larger and larger but still resistive and still fragile. You still had to battle dust and dirt if you wanted to keep your PDA screen pristine.

Time moved on and Psion gave up on the PDA market - sadly. Microsoft got in on the action with their Pocket PC-based PDAs, also with resistive touchscreens, getting ever larger, up to 4" in some cases, matching today's large screened smartphones. Palm went through their own purple patch with the V and Tungsten ranges, with screens again getting larger and larger but still resistive and still fragile. You still had to battle dust and dirt if you wanted to keep your PDA screen pristine.

All of which sounds like a huge problem but it wasn't really, since the touch interfaces concerned were almost exclusively concerned with screen 'taps', i.e. indicating a spot on the display, perhaps pressing a virtual button or positioning a text cursor. (The one exception was in text input, mainly on the Palm devices with their famous 'Graffiti' areas - these saw heavy use of gestures for entering text and, not surprisingly, ended up being heavily scratched on much-loved units.)

The same 'tap-centric interface' ideas applied to a large extent to Nokia's touchscreen-driven 7710, back in 2004, to all the UIQ-touch phones, and to the S60 5th Edition smartphones that debuted with the 5800 in 2008. There was simply no desperate need to use gestures or swipes, and tapping away with a plastic stylus or a finger was quite sufficient, even for text entry on the virtual qwerty and T9 keyboards and keypads (shown right).

Apple, meanwhile, had introduced the innovative iPhone mid 2007, written from the ground up to make full use of capacitive touch technology, a radically different system that sensed finger capacitance from behind glass and which was optimised for smoother, more continuous touchscreen use. Capacitive screens are/were inherently less accurate in terms of resolution (just one of the points I made at the time, pointing out that both touch technologies did have their pros and cons; although capacitive accuracy has improved a lot in the last two years), but are far more pleasant to use in terms of gestures and in terms of an 'organic' touch interface.

As use of touch interfaces then evolved, with increasing use of swipes, 'pinches' and even multi-touch gestures, it became obvious that the old 'tap to indicate a spot on the display' technology was becoming increasingly outdated, a point I acknowledged in a subsequent editorial. Touchscreens really needed to be swipe-friendly, which meant that capacitive touch on glass was the way forward, cost-permitting (the cheapest phones will probably use resistive touch tech for a year or two yet).

But.

Just as important as the switch to capacitive sensing has been the use of glass for the front of the display, much tougher to accidentally scratch and damage than plastic. The original iPhone used traditional glass and was somewhat shatter prone if dropped. But the trend to glass had started and we then saw even the non-touch Nokia N86 with tempered glass, then the Motorola Milestone (running Android) with 'Gorilla glass', a branded, optimised, aluminosilicate glass with near-indestructible properties. Subsequently, we've had other Motorola devices, many Samsungs and all the new Nokia Symbian^3 smartphones, all with Gorilla glass, either explicitly stated or implied by the manufacturer. Even the iPhone 4 has now adopted a form of the same glass, apparently (though not Gorilla glass explicitly).

Here's a demo of Corning's Gorilla glass at work (on a larger TV display, but you get the idea):

Which means that I can now perform the above-mentioned party trick with my N8 or any of a number of other devices. Away from kitchen knives, it also means that, at long last, we don't have to treat our touchscreen devices with kid gloves. Or screen protectors. Or silicone polish. We don't even have to get out a plastic stylus, or use a fingernail - neither of which would work anyway because there'd be no human electrical contact.

In short, the modern smartphone, epitomised by Nokia's N8, E7, C7, etc., can be chucked in a handbag or pocket with keys and coins and general day to day detritus and there's more chance of the phone scratching the other objects than the other way around. I was listening to a UK podcast the other day where a guy was being particularly ignorant by claiming that the Gorilla glass on the camera exterior on the N8 was scratched just by sliding the phone on a restaurant table. Firstly, the glass is slightly recessed, so this is physically impossible, and secondly, the glass is much harder than the table - if I were him, I'd have been apologising to the restaurant owner and making sure the table hadn't been damaged...

It's hard to see where touchscreens can go from here. They're now accurate enough for manipulating even high resolution displays under the glass. They're just about indestructible. ClearBlack Display and anti-reflective filters (and similar) under the glass mean that contrast is now good, even in sunlight. Yes, displays will continue to get larger - or at least fill in the continuum between a 2.4"-screened pocket phone, a 4"-screened smartphone and a 7"-screened tablet, but technology-wise and certainly touch-wise, touchscreens are now fully mature.

As hinted in my opening paragraph, the rest is up to the programmers 'behind the glass', the people who create the objects and elements that get displayed and manipulated. That's where there's still magic to be created.

Of course, show a modern smartphone (say, an N8 or iPhone 4) to a Psion or PalmPilot user back in 1998 and the super-robust, super-sensitive, super-high contrast screen would seem like magic, proving again Arthur C Clarke's third law!

Steve Litchfield, All About Symbian, 13th Jan 2011

PS. Bonus link to Corning's Gorilla Glass site