The human brain is often cited as the most complex object in the universe. Whether that's true or not (and it depends on your definition of complex), there's no question that the brain is capable of absolutely astonishing acts of recall. Most of us would be able to sing entire songs based on the first few notes or even just the title, or recite long poems, or give the dates and details of important historical events. The amount of information we can immediately remember with high precision is amazing.

So, given that we are all equipped with the greatest biological computer ever made, why do we have so much trouble remembering ten-character passwords or even four-character PIN numbers?

The answer is, of course, the context: all of us can remember complete pieces of music, but very few of us could remember an equivalent amount of random notes. Our brains are clearly built to recall things in context, probably because they use context in compression techniques. Data compression works by editing out repeated sequences, but written passwords and PIN numbers are supposed to avoid repeated sequences because they would be a security risk.

And that's the dilemma: we find it easy to remember huge amounts of data in context, but if a password is based on context it may be much easier for other people to guess. How do we get the easy-to-remember benefits of context-based passwords without giving up the hard-to-guess security of random passwords?

Warp speed, Mr Sulu

This writer recently watched some original 1960s episodes of Star Trek, and one prop which comes up again and again is an electronic document reader which periodically requires the captain's signature to authorise orders:

In case you're wondering, this is an episode called "The Deadly Years" where Kirk ages too quickly.

To modern eyes this seems quaint and old-fashioned, which is probably why physically signing electronic documents was abandoned by later Star Trek versions. But is this kind of technological snobbery sensible? Could the simple timeless act of writing your own name in your own style actually be the best way to combat password fatigue? Might we all one day be using signatures on computers, just like the 1960s crew of the Enterprise?

On the surface, a signature seems dangerous to use as a password because anyone who sees it on a printed document (such as a driving licence or passport) could copy it. However, Captain Kirk did not sign things by uploading an image file, he signed things just like we do today, by constructing his signature in a series of specific pen strokes. A device with a touchscreen would be able to detect not only what the finished signature looked like but how it was written, including the speed, sequence and (possibly) pressure for each component. Such elements could not easily be discerned from the finished signature, yet they would be instinctively known by the true owner of the signature.

Perhaps people who need to prove their identity online could simply write their names, just as they have done for centuries with paper documents? They wouldn't even need to invent a password, everyone knows their signature throughout their lives.

Security through doodling

This isn't a new idea, there have long been systems developed for measuring and analysing signatures, but so far no major online company offers their use instead of passwords or PIN numbers. It could be that signatures aren't quite as uniform as we think they are, and even if they are there is a risk in putting all your security eggs in one basket. If someone managed to get a recording of how you signed your name then they'd be able to copy it exactly, and you'd have to change your signature which is a lot more difficult than changing your password or PIN.

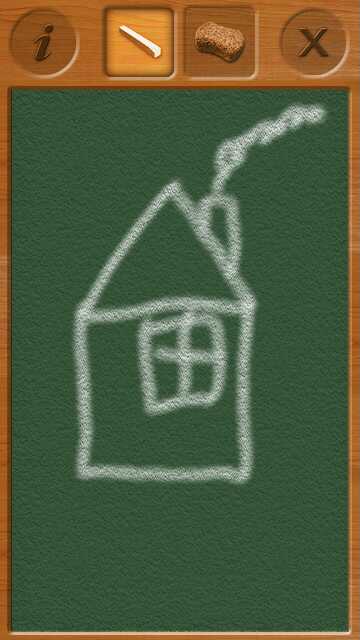

But other context-based passwords using a pen are also possible. One popular technique for memorising a piece of information is to associate it with something visual. What if instead of writing a signature people drew a picture? The same kinds of style data present in handwriting could be detected in handdrawing, and a user could have different pictures associated with different services. You might draw an envelope in a particular manner to access an e-mail service, or draw a musical note in your own style to access your online music collection. As long as you draw it in a reasonably consistent way, and as long as no one saw you drawing it, such image-based passwords would be much easier to remember than the random kind we're supposed to use now.

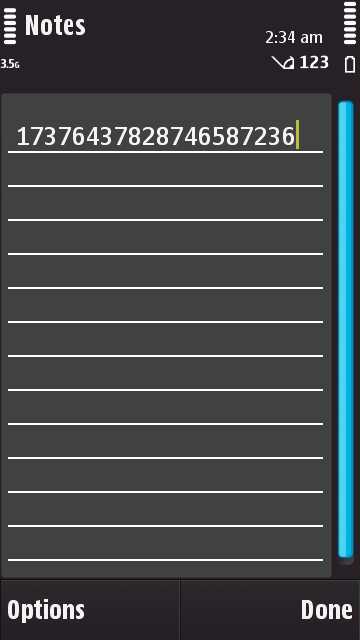

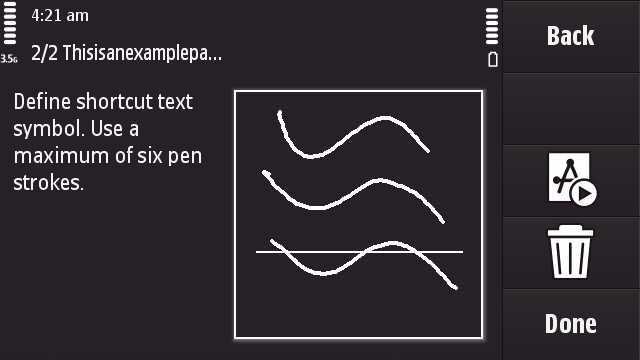

Two potential passwords entered on an N97. Which one would you find easier to remember?

The numbers on the left are much harder to remember than the drawing on the right, yet the drawing could act as a much more complex and secure password. If the phone was able to record how the drawing was constructed, it would be impossible for outsiders to copy simply by looking at the finished picture.

Obviously no one wants to draw a picture every single time they do something on the internet, but no one wants to enter a written password every single time either, which is why most people use cookies or browser memories to store passwords. Those same features could be used to store visual passwords too.

Could Symbian help graphical passwords take over from written ones?

Using drawings as passwords isn't a new idea either, but what is new is the potential means to deploy them. Until now, very few people owned an electronic device they could draw on. PDAs have been touch-sensitive for decades, but they have always been an expensive niche item bought by small numbers of people. What is needed for graphical passwords to take off is a mass market device which is cheap enough for large numbers of people to afford, and attractive enough for them to want to actually buy it. The mobile phone certainly fits the description of being mass market, there are about 1000 million mobiles sold every year which is far more than any other electronic product. However, these are almost all button-based phones. For graphical passwords to become standard, the majority of phones would have to be touch-based, which hasn't happened yet, and is unlikely to happen as long as touch-based phones remain expensive.

And that's where Symbian comes in. The latest version of Symbian S60 is touch-based, and has been deployed very successfully on the Nokia 5800, which is selling at a rate of over one million units a month. That's only a small part of the 80+ million mobile phones sold globally per month, but it's a much larger proportion of the smartphone market and it's a lot more than any PDA ever sold. What's more, over the last few years Symbian has been appearing on ever-cheaper models which can reach ever-larger audiences. The 5800 itself is a relatively low-cost smartphone, at around half the price of the N97 or iPhone, and there's an even cheaper model (the 5530) due to be released very soon. Within a few years, we may see touchscreen phones at the lowest end of the market, and it's the lowest end that makes up the majority of sales.

Because touchscreen phones have been historically expensive, no one knows if they can ever replace button-based phones, and it's possible that most people will carry on preferring to use buttons. But if touchscreen phones do eventually take over the phone world, they could be the most powerful weapon in the war against password fatigue.

Password fatigue is not a trivial issue. Many security breaches are caused by people using the same password across several services simply because they cannot remember more than one or two passwords. Other breaches are because written passwords are too easy to guess. Graphical passwords are easier to remember, more intuitive to enter and potentially more complex than written ones, so they could make the internet not just easier to use but also a lot more secure.

Symbian offering a taste of the future?

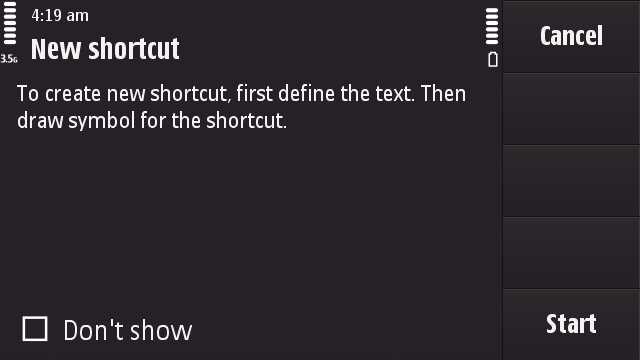

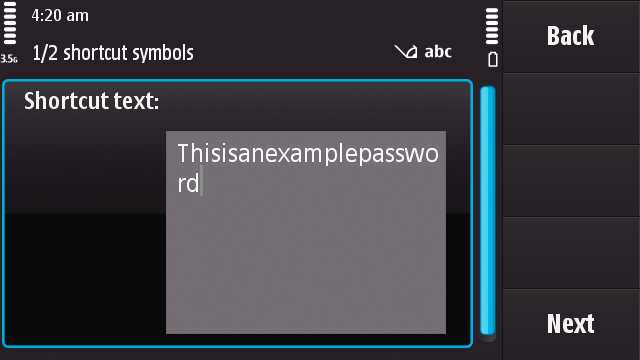

In fact, we have a piece of this potential future in our hands already. You can actually use pictures as passwords right now on Symbian S60 5th Edition devices such as the Nokia 5800 or N97. Their handwriting recognition input method has a learning mode where you can teach it, to associate strings of text with particular doodles. If you associate particular written passwords with particular doodles, you could use doodles to enter passwords. (This can also be done on Nokia's Maemo-based devices like the N800 and N810, using exactly the same process.)

(Author's note: Unfortunately the current version of the S60 handwriting recognition system seems to have too many preset characters in its database, so most doodles you suggest are rejected as duplicates. If anyone from Nokia and/or Symbian is reading this, can you greatly reduce the number of default preset characters used by the system? The system would work much more effectively if it only used characters from the currently-selected language.)

Tzer2, All About Symbian 23rd August 2009