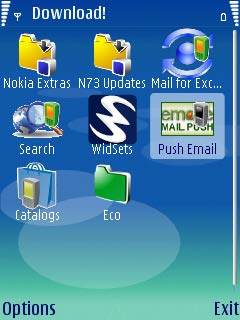

On-device app stores started with Nokia's Download! system, circa 2006, of course. The experience was very bare bones and the number of apps was artificially limited by Nokia, for good or bad. The end result was that it was useful but not world-shattering. What was needed was something far more open.

On-device app stores started with Nokia's Download! system, circa 2006, of course. The experience was very bare bones and the number of apps was artificially limited by Nokia, for good or bad. The end result was that it was useful but not world-shattering. What was needed was something far more open.

Enter Apple and its iPhone App Store in 2008. The combination of powerful hardware which invited ambitious titles (especially games), a relatively easy route to development and, most of all, an on-device store which almost anyone could get into (subject to approval, i.e. conformity with Apples Terms and Conditions). The result was an overnight success and two years later we have 100,000+ applications listed. Yes, 95,000 of these are trivial novelties, but the download numbers are still mightily impressive.

So what happens in this world when an application gets updated by its developer? The on-device App Store client notices that an installed app has an update and marks the App Store icon with a little numeric flag (to indicate how many apps need updating). It's then up to the user to want to start up the App Store client and then either tap on applications to update them manually or accept a batch of updates with 'Update all'.

To be honest, this is fairly painless, but it does require some user interaction - I picked up my daughter's iPod Touch just now and the App Store client was showing no less than 34 apps needing updating! Clearly this aspect of computing was something she didn't pay any heed to - and I suspect she's not alone.

Under Android things are (on the whole) worse at the moment, in that a manual trip into the Market (depending on device, you may also get notified via the top notifications bar) will show you, under 'Downloads', what's waiting to be updated, but you have to tap on each explicitly and, worse, acknowledge two extra dialogs - per application. Under the upcoming Android 2.2, there's apparently an 'Update all' option, as with the iPhone, though developers will need to embrace this for their apps to be included.

And so to Symbian, the world marketshare leader for smartphones by a country mile but rarely perceived as such by the media. Nokia, by far the biggest partner of Symbian, has its Ovi Store, a serviceable app store that followed the iPhone's lead but which is evolving at, some would say, glacial pace - not helped by being implemented as a glorified Web runtime widget, i.e. a dynamic web page. There's no concept whatsoever of application versions on the store and no official way to notify users who have already downloaded something. Apparently it's 'on the roadmap' - though with Nokia World 2010 just around the corner, it's possible things might change next month.

Sony Ericsson's current Symbian phones rely on an even clunkier Web-based system, involving multiple instances of Web that just eat up the OS and with no apparent advantages.

Sony Ericsson's current Symbian phones rely on an even clunkier Web-based system, involving multiple instances of Web that just eat up the OS and with no apparent advantages.

At first glance then, the iPhone seems a slam dunk for first place, followed by Android and with Nokia in a distant third, in terms of application updating. However, I contend that all this isn't necessarily the only - or indeed right -way to update applications in the first place.

Moreoever, it could even be argued (you may want to lie down for this contentious opinion) that Symbian is even vying for the lead in terms of smartphone app updates - not because of manufacturer app stores - the places where a user discovers apps in the first place - but in spite of them.

You see, with no auto-update notification system in place from the OS itself, or from an app store, applications have to check themselves for an update, direct from the developer's servers. This has two huge advantages:

- the user doesn't have to lift a finger. When an app is started (or on a regular schedule), it goes online and checks for an update automatically, in the background, prompting the user to press 'Yes' to download and install an update if appropriate.

- updates obtained from the developer's server will be bang up to date and not a month or too old (as is usual after passing through some approval process). In the case of the famous Gravity social network client, you even get access to alpha and beta versions this way - very cutting edge.

All of which sounds wonderful and yes, if every Symbian application (and game) did this, then it would be blatantly obvious that this is the best way to go. The only slight fly in the ointment is that not many developers seem to want to implement this. There are obvious significant technical hurdles to overcome to work out how to handle update requests online and serve up updates if needed, but this is clearly the way to go. Some Symbian apps aim for a halfway house, checking for updates and displaying the result on a web page, rather than in the app, so that at least you're in the right place to make the download, though we're then back to things being rather manual and not quite as ideal.

It's worth noting that a similar small number of Android applications also 'dial home' for updates in this way, but again these are very much the exception rather than the rule.

One possible disadvantage of the auto-checking for updates is that the user might incur extra data charges, but I'd dismiss this by noting that a) update checks rarely involve more than a few kilobytes of data and b) if a programmer is clever enough to implement auto-update checking and downloading then he's clever enough to also check that the user is connected via Wi-Fi beforehand.

How many other Symbian applications emulate Gravity and automatically check for updates online, with no involvement from the user or any need to boot up the web browser? I'd love to know. I'm guessing only a handful - can you help out in the comments below?

The best and most comprehensive solution all round is probably to have the best of both worlds. An app store which tracks version numbers and can flag up any updates plus independent version checking by the apps themselves, direct to the developers. In truth, each system has its advantages, but as they're not mutually exclusive then why not have both in place, to catch all users, whatever their app usage pattern?

Steve Litchfield, AAS, 30 August 2010