So let's start on those terms and conditions. First up, the £30 unlimited is capped to £500 equivalent value, when your usage is placed alongside the listed call charges... with data at £4 a megabyte that limits your internet use to only 125MB for the month (i.e. only 4MB a day), assuming you make no other calls – you're essentially mixing that 125MB alongside 2,500 voice minutes or 5,000 texts till you reach the capped value.

Putting aside the crazy limits on data, flat rate plans are a great idea for the consumer. They help them budget and can prevent bill shock when the end of the month comes along. Rather than husbanding your phone for emergencies, you can let rip and call and text and you would have to go some to break that limit in a month. A far cry from my first contract which offered me a heady 15 minutes free a month back in the 20th century!

Data is a problem them, because it's becoming a fabric of not just the limited smartphone space, but the mid and low tier handsets. Google Maps, available as a java install for pretty much every phone on the market, downloads the mapping data as it is needed. How long would it take to eat up that 125MB? About as long as it takes you to get to the nearest shopping centre would be my guess [methinks Ewan exaggerates, a local Google Maps journey should only use up a few hundred KB - but I take his point - Ed]

Two things are holding back adding realistic 'unlimited' data (not least that people have a different understanding about the word unlimited than telecoms companies have). The first is physics and the amount of bandwidth available for 3G data connections. Put a large collection of unlimited data handsets in close proximity and the current infrastructure struggles to cope. London has just seen “The Future of Web Apps” conference and the geekerati were out in force. For some reason, O2 was unusable and the reason was simple... the number of unlimited data O2 iPhones. (It'll be slightly better at the Symbian Exchange and Exposition, thanks to spreading data out over half a dozen networks)

The second is partly related to the first. Fear. The fear that opening the floodgates will totally destroy their network and reputation is probably valid given the problems above, but I think they're just going to have to suck it up and get with a program to upgrade their networks and make it work. For all the problems and localised headaches, the unlimited data for the iPhone on monthly (and pay as you go) on O2 has not crippled the network – just pointed out the flaws. For all the problems with that device, Apple the company had enough swagger to force through something unpalatable to the networks, and now T-Mobile/Orange and Vodafone are joining the party. The crack in the door is already there.

And the one thing networks can't do is go backwards.

The situation feels very much like the last days of metered dial-up internet in the UK, back in the last century. The final hold out was AOL, who stayed on per minute charges after everyone else had switched over to a fixed monthly charge. They were worried about the number of modems they had available, that people would get an engaged tone on dialling in, with people just staying connected and doing nothing. The per minute charge was less an income and more a way to try and stop people staying connected.

Hunt around on the network tarriff pages and you'll find offers that help you control the billing of data, for example Orange's up to £1.50 a day for 25MB of data that you can add to a monthly contract or, to a lesser extent, Vodafone's 3GB per month for £15. But they're still limited to amounts of data that you have to monitor, and the costs are still measured in pounds per megabyte once you go over the limits. It's a start, but not ideal.

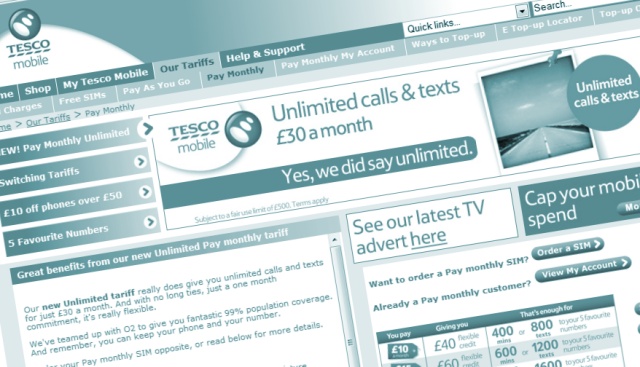

Tesco Mobile's "unlimited" offer

Technology and traffic shaping have moved on a lot since the millennium, as have customer expectations. You want a prediction? Unlimited data tarriffs will become the norm, probably late in 2010. One network is going to open the floodgates and just go for it as a marketing campaign, and the others will have to follow. The question is which companies are going to stare down each other to be the first to see what happens to their network when they do throw the switch.

-- Ewan Spence, Oct 2009.