First up, some basics on who pays for an application. There are three base methods, the most popular being the user paying the developer for the application.

The second has the developer paying for the application, by virtue of giving away his time and expertise. There may be reasons for that, perhaps this is an application being released to increase his visibility, to promote his skills - I can even forsee some using a release for tax write-off reasons!

You could also argue that there is an additional way of paying for an application by mixing these models, when a big company (e.g. Orange) commissions a team of developers (like Future Platforms) to write up an app (say for Glastonbury) that Orange can give away. In my mind that’s a third party paying, although the money and income is agreed up front, and then it can be given away. So you can argue where it fits in the three models, but it does fit.

The third way has gained prominence over the last year or so, and that is having a third party pay to gain access to the users of the developers app. This is the classic model of advertising, but brought into the early 21st Century landscape of smartphones. Smart eyed readers will spot this series on monetising applications is supported by inneractive, who deal specifically with in-app advertising, but before we address this new method of doing business, it’s only right that we look at the existing model that still serves many developers well.

The app stores have seen a tweak in how software is sold. Smartphones (and their PDA predecessors) thrived on shareware, where the user would make one download of a demo application, and if they liked it could buy the full version, which generally involved an unlock code being sent to them that would release all the functionality. It was rare that another version would have to be sent out by the author.

Now that there is a central distribution and engagement point, that model has changed slightly. Although you still can run your business on a website, it's far easier to get seen in an App Store than getting people to a single website (but you still need a home for marketing purposes). And because of the nature of App Stores and how they take payment, it has become the norm to replace the single application with two modes (Demo and Full), i.e. with two separate versions of an application.

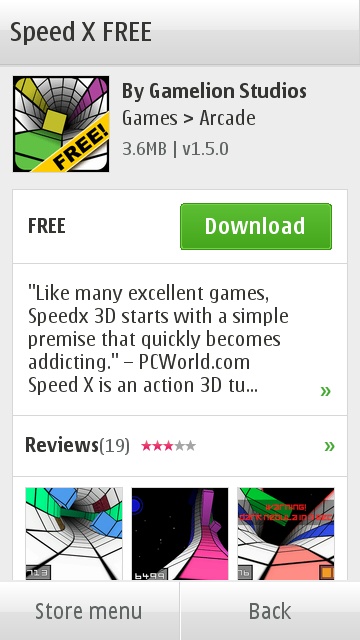

Thus we have the rise of the “Lite” application that advertises the “Full” version of the application. Looking through the Ovi Store, around 7% of regular applications (i.e. those that aren’t generated by the Ovi App Wizard) have “lite” or “trial” or "free" in their name.

Same title, two apps in the Ovi Store, the free demo and the full game.

Growing out of the original shareware “registration key” system, this dual application model is now something that people expect and understand. That factor is one of the most important considerations for a developer, who needs to think about how they are going to be paid - but with new tools, always-connected devices, and available bandwidth, it’s not the only consideration.

The biggest of those is that this is a one-off payment. The user buys the application, they download, and it’s on their device for as long as they want it. It’s likely that the relationship you have with the customer will go no further than this - sure, there will be some people who interact around bug fixes and looking for potential new features, but they will be a small percentage of your user base. Once the payment is made, you’re not going to see anything else, but yet there is an expectation on you to provide ongoing support of the application, especially if you’re going to need to code and release another application to keep your cash flow up, or rely on solid word of mouth to keep up a constant stream of new users.

The other way around this problem is to raise some more income from your existing users, and that’s where it get interesting, and a touch innovative.

One way of doing this is to say that when you make the purchase, you get the current version of the application and a number of updates. Once a certain version mark has been passed, you’d need to purchase again to get a hold of the latest code. It’s an approach used by Quickoffice in their office suite of applications, allowing a smartphone user to edit and create spreadsheets, presentations and documents. On buying the application you’ll be able to download the updates provided for that version, but when the application bumps up a major version number, you may not be eligible for the update with all the latest code and work.

Quickoffice is present in a number of Nokia smartphones, although often in a limited view only form - if the user wants extra functionality, they can buy the extra features from inside the application - a tweak on the shareware principle above, but one that illustrates the power of in-app purchasing. Do note that by being bundled by Nokia in all the smartphones, Quickoffice to have a larger base to exploit, and could look at a solid credit card purchasing system they implemented themselves. That’s not available to every Symbian developer.

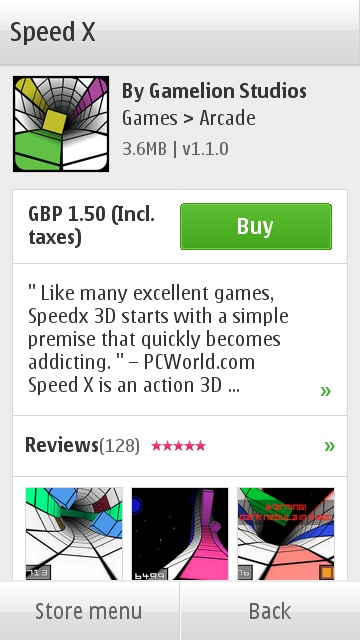

What may be a viable option is Nokia’s in-app API that allows purchases to made with the user’s Ovi Store account, but from inside the application. You can find more details on this at Nokia’s Developer site, but it’s worth pointing out that, beyond one showcase example we’ll come to in a moment, we’re not aware of this being used “in the wild” by any developers. It’s still labelled as being in alpha for C++ apps and beta for Qt apps in Symbian^3. It would be be fair to say that, while the option is there, it’s not yet proven in the Symbian marketplace.

A demo of Nokia's in-app purchasing system.

In-app purchases have proven successful for developers on other smartphone platforms, notably iOS. There have been a number of applications using a strategy of being free to download, but only offering certain additional features if they are purchased by the user. iOS developer Noel Llopis has been upfront about his income from Flower Garden, and the difference that in-app purchasing made to his income; around four in ten users have purchased the Mighty Eagle to help them get through a particularly difficult level of Angry Birds; Tiny Tower, a Sims like game where you build a skyscraper of shops and apartments to be populated, is an almost textbook example of an app that is free to download and can be free to play, but to accelerate the game you need to buy in game credits using real money. Given the label “freemium”, this idea is fertile ground for developers using in-app purchasing.

It’s unfortunate that Nokia, who have a clear lead with the networks to provide carrier billing via the Ovi Store alongside the regular credit card payment methods, haven’t made more of an effort to make in-app purchasing a worthwhile choice for developers to use and innovate around - this is very much a missed opportunity.

While both these techniques may feel new, they are essentially taking two angles - the first is the shareware concept but in a very broadly defined time window. I could easily see Quickoffice discussing if the “one major and as many minor versions” model could be switched to “everything within a nine month window” model, although I do think they have the balance about right at the moment - and Rovio actually cover all the bases with sales of their application on Symbian and iOS, working on a movie tie-in for Angry Birds Rio... and funding their Android version of the game solely with advertising displayed in the game.

It’s that final approach that is catching the eye of many developers. It reduces the barrier of entry for a user (free at the point of download) and it provides a recurring revenue stream (assuming that the application is good enough that people will continue to use it). But the answer is not to simply drop some adverts into the application just before you post it to an app store - especially if the application was designed to gather one-off purchases or conversions from a free version. You need to consider how to place adverts in your application as early as possible in the design phase, to choose partners carefully, and to make sure you balance the needs of the user, the advertising, and yourself as a developer.

And that’s what we're going to look at next.

-- Ewan Spence, August 2011.

'Supported content' series, in conjunction with a third party, allow us to explore topics in more detail than would otherwise be possible. Typically, this is for topics that have a smaller audience than our usual content.

In supported content series, All About Symbian retains full editorial control, with each part written and edited by the AAS team.